Restoring Your Old Photos

by Gerry B/ackwe/l

It's a rare household that doesn't hoard shoeboxes full of old photos of family, friends, birthdays and Christmases past, long-ago beach vacations and grand tours of Europe.

The older the pictures, the more scratched, creased, speckled, faded and generally unviewable they are. But you can turn the mouldering photo collection problem to your advantage this holiday season.

Use your home computer, a scanner and photo-imaging software to restore some of your best old pictures. Then print them as album pages, with captions and dip art if you want to get fancy. Bind the pages and give personalized albums as Christmas gifts.

Professional photo restorers charge a fortune to restore old photos, but now relatively inexpensive digital tools make it easy for anybody to do. Here's how.

What you'll need

PC: You can do digital photography with just about any computer built in the last three years. But with anything less than a 400-MHz Pentium with 128MB of memory, you may be frustrated at how slowly it works.

Scanner: The scanner, which converts prints (or slides or negatives) into more or less faithful digital copies you can store on your computer, is vital. You want a flatbed model with scan resolution of at least 1,600 dots per inch (dpi) and colour depth (a measure of the range of colours the scanner can reproduce) of at least 32 bits.

There are lots of great, inexpensive scanners out there. Canon, Epson, Hewlett-Packard and Microtek are all good brands.

We tried the new Epson Perfection 1670 (about $130). It's inexpensive, and offers relatively high scan resolution (1,600 x 3,200 dpi) and colour depth (48-bit). It also lets you scan negatives and slides, which not all flatbed scanners do. One of the really nice features of the Epson 1670 is that it comes with automatic colour-correction software that can fix old colour prints or slides as you scan.

Software: Finally, you'll need a good photo editor. Two of my favourites are Photolmpact 8 from Ulead Systems ($120) and the new Paint Shop Pro 8 from Jasc Software ($150). There are lots of other good ones, though, including Microsoft Digital Image Suite ($140) and Adobe Photoshop Elements ($UO).

Colour Correction

Fixing faded colour pictures may be the most difficult photo restoration job. Colour is very tricky, especially if you don't have an eye for it, which I don't. Luckily the Epson scanner's automatic correction feature made it pretty easy.

I started with a picture I thought was a no-hoper: a 48-year-old snapshot taken aboard the S.S. Oronsay enroute across the Pacific to Australia. (My family was heading to Oz for a year's sabatical.) It's Equator-crossing day and the crew is putting on a show. King Neptune and his cronies are getting ready to hurl the kids into the pool: an old tradition apparently.

The three-by-4.5-inch original is faded to the point of being virtually monochrome, but with a rosy cast. It's also scratched and speckled and there are odd blotches of green and aqua — possibly mold.

My first scan looked pretty much like the print. Then I turned on the Perfection 1670's colour-correction feature. Immediately the greens and some other colours showed up and the skin tones, always the most difficult to get right, began to look a more realistic. It wasn't perfect, though.

Next I opened the scanned image in Photolmpact and adjusted the hue (which shifts the colour of each pixel by the same amount) and the colour balance (which adjusts the balance in the picture between complementary colour pairs such as blue and yellow). I also fiddled with contrast, brightness and sharpness and cleaned up the blemishes (see below).

As you can see, the finished picture is still a long way from perfect. In fact, the restoration process introduced a new problem: the loss of detail in the sky and sea in the background. A professional might be able to do more, but at least now we can see what's there, including expressions on people's faces.

Out Damn Spots!

Removing the scratches, creases and specks that mar old pictures is often easier to do than colour cor rection, but can still get tricky. I started with another 1950s photo, a black-and-white snap of a small boy with a toy pipe in his ; mouth. There's a big crease across one corner, multiple shallow scratches where the emulsion has been abraded by other pictures stacked on top, and countless specks: either bits stuck to the sur- j face or places where the emulsion has been pitted and the paper below shows through.

This 48-year-old old photo, taken during on Equator-crossing day during an ocean voyage from Canada to Australia, was badly faded and scratched.(Left)

Using the Epson 1670 scanner's colour-correction software, then adjusting contrast and colour settings using an image-editing program, dramatically improved the picture. (Right)

Cloning: The "traditional" way to remove blemishes using digital imaging is with a clone brush. The Photolmpact clone tool is typical. You select the tool, hold the keyboard shift key down and left-click on an area of the picture similar to the area hidden by the spot or scratch. Now click and drag the cursor over the blemish.

The clone tool takes pixels from the clean area where you clicked first and copies them wherever you drag the cursor in the second action. You can fine-tune the tool: adjust the width covered when you drag the cursor, the level of transparency of the copied pixels, the softness of the edge and other attributes.

Using the clone tool works great

for small blemishes. It becomes very difficult, however, when you're working with larger areas, especially where the blemish covers parts of the picture with shaded contours. Finding the right area to clone over can be nearly impossible. If you look closely at the picture used in the section on colour correction, you'll spot various places where cloning is all too detectable.

Using the cloning tool on a very messy picture is also tedious and time-consuming. You need to view the picture at actual size and methodically scroll up and down looking for marks to remove. If cloning from one dean area doesn't look right, backtrack and try a different area.

Automatic cloning: Pa/ntShop Pro relieves the tedium. It includes an excellent set of automated cloning tools. To remove large scratches, for example, you select the scratch-remover tool, left-click at one end of a long scratch and, holding the mouse button down, drag out the rectangular boundary box, keeping the scratch inside it. When you've dragged it to the end of the scratch, take your finger off the mouse button and, presto, the scratch is gone.

I used this tool to remove the crease in my test spicture. It took more than one pass because the creasing caused several scratches in the emulsion that weren't perfectly straight. When the crease was gone, I started on the lighter scratches, of which there were many more. Still, it only took a few minutes.

Now I was left with the specks and small irregular scratches. Most photo editors have Despeckle filters that can remove spots automatically using the cloning principle. Many don't work well, but the PaintShop Pro tools work superbly. I used three: Despeckle, Small Scratch Remover, Salt and Pepper filter (for tiny dark and light specks). Within seconds, I had a clean copy of the picture.

One effect of a lot of cloning can be softened focus. To finish, I used PaintShop's Sharpen filter to make the restored picture a little crisper.

This 1950s black-and-white photo had a long crease and several smaller scratches and specks. (Left)

Using the cloning and despeckle tools of a photo-editing program got rid of the damage, and the sharpen tool helped make it crisper. (Right)

Presentation

Once you've restored some great old pictures, create and print album pages to bind and give as gifts.

Some photo editors have album page layout options. If you want fancy pages with graphics and text, use a desktop publishing package such as Microsoft Publisher. You might even want to splurge on a product like The Big Box Of Art from Hemera ($45): a collection of 350,000 graphics, photos and textures.

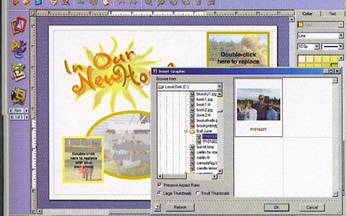

A scrapbooking program such as krapbook Factory Deluxe ($55) from Art Explosion can automate the page-design and layout process. It includes dozens of page templates with modifiable graphic decorations and text. Choose a template, modify the text, then click on the picture boxes to add your own pictures to the page.

Art Explosion will sell you binders, or you could use three-hole albums from a photo store, or make your own hard-bound photo books using the method we described last issue. (See HH, Vol. 2, No. 3, Summer 2003.) *

Scrapbooking programs like Scrapbook Factory let you make printed albums that you can give as gifts.

Personalized Holiday Cards

Make your own personalized photo greeting cards using a recent family portrait, which you can take yourself by putting your digital camera on a tripod and using the self-timer. In your photo editor, dress it up with a border.

You can make simple cards with nothing more than a good word processor. In Microsoft Word, use File/Page Setup to start a new landscape page with half-inch borders all the way around. We're going to make a single-fold vertical card, with final, folded dimensions of 8.5 by 5.5 inches.

Use Table/lnserf/Table to create a table with one row and three columns. Use Table/Properties to set the cell width for each cell separately. The one in the middle, where the fold in the card will go, should be one inch. The two outside cells should be 4.5 inches each; this is where you'll put your content. The height for all three should be 7.5 inches. Use Format/Borders and Shading and select None.

Save the page as xmascard.outside. Then use File/Save As to save a second copy as xmascard.inside.

Re-open xmascard.outside. Place your cursor in the far right-hand cell; this will be the front of the card. Select Insert/Picture/From File and use the standard file browser that pops up to find and select the previously saved family portrait. Click OK and the picture will fill the cell.

If it doesn't fill the cell, dick and drag the little box in the bottom right corner until the pictures is as wide as it can be and still stay within the cell boundaries.

Here's a little refinement: place your cursor in the left-hand cell (the outside back of the finished card) and select Table/Properties, then click the Cell tab. Change the vertical alignment to Bottom.

Type the name for your card company (Blackwell Cardworks, say) in a small, distinctive font and centre it. Select Insert/ Symbol and insert a copyright symbol - (c) - before your wordmark. Very professional.

Now open xmascard.inside. Put your cursor in the right-hand cell; this will be to the right of the fold inside when you open the card. Use Table/Split Cells to split the cell into three rows. Put your cursor in the new middle cell and type your greeting using a big, fancy font. You can add seasonal clip art in the other two cells or in the left-hand cell.

Buy 8.5-by-11-inch pre-folded

card paper or heavyweight semi-gloss photo paper printable on the verso (i.e. it shouldn't have manufacturers' watermarks.)

Print xmascard.outside on the good side of the paper. Wait until the ink dries, then put the paper back in the printer to print the other side. Getting the paper in the right way around can be tricky. Practice on plain paper. Then print Christmas card.inside on the "bad" side of the photo or card paper.

Wait until the ink dries and fold the card. Et voila, you're done.

Of course, you could make it much easier on yourself and invest in a good desktop publishing program or a dedicated greeting card program such as Hallmark Card Studio 2003 ($40) or Greeting Card Factory Deluxe 2 (about $50). These programs come with thousands of pre-designed cards, many of which you can personalize by adding your own photos. *

Using the table functions in Microsoft Word, and then inserting images and composing text, you can make your own home-made cards.