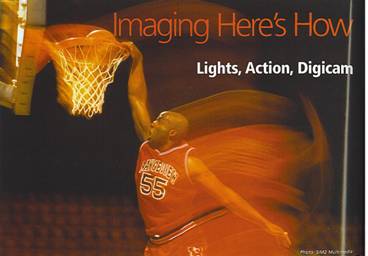

Using the slow flash option enabled the photographer to con

vey motion during this exciting jump shot. The short

duration

of the flash helped keep the basketball player and ball

clear,

but the slow shutter speed produced blurring that

conveyed

the sense of motion. In this shot, the flash was fired at

the end

rather

than the beginning of the shot, so that blurring is

behind the subject. ..

.. ,

by G B

You can use your digital camera to capture action and make great still pictures. This may sound contradictory, but it really isn't.

A single image can't capture motion the way a camcorder does. But good action stills can sometimes be more dramatic and evocative than video.

By action, I mean just about any kind of movement. It could be kids frolicking, a bird in flight, a dramatic moment in sport. It could be a raindrop splashing in a puddle.

You need only basic equipment. Most digicams work fine. However, digital cameras are usually slower to react than film cameras, so you may need more practice to master snapping at just the right moment, slightly ahead of the action.

Tip: Another way to make sure of capturing the right moment: set your camera to take multiple pictures while you hold the shutter down, and start shooting as the moment approaches.

Long telephoto lenses and high-ratio optical zoom lenses like the ones on the cameras in our survey of ultra-zoom digital cameras (see "Imaging Hands-On," page 32) are useful for getting you closer to the action when photographing wildlife or sporting events. But you don't need them to shoot many action subjects.

A more powerful flash than the one built in to your digicam may help properly illuminate some subjects, but again, there are lots of situations where a relatively simple camera is all you need.

You will need a little photo know-how, though, and a few basic skills. Planning helps when taking action shots too.

You can divide action photos into three broad types: those in which the person or thing in motion is blurred while the background is in sharp focus, those in which the subject is more or less sharp and the background appears blurred, and those where you freeze the moment.

Each has its place and each its techniques. Part of the trick is knowing which to use for a given subject.

Here's How to Freeze Action

Freeze action when you want to capture the drama of the moment or see exactly what happened in detail: a runner hitting the finish line, your kid connecting with the T-ball, baby's first wobbly step.

Tip: Freezing action doesn't work well when the subject is a moving vehicle. Even racing cars look like they're standing still, which is not terribly dramatic.

To freeze action, you need a camera that allows you to control shutter speed (the length of time the lens stays open to let in light, measured in fractions of seconds or seconds).

Most advanced cameras have a "shutter-priority" mode that lets you manually choose a shutter speed. The camera chooses the appropriate aperture (the size of the lens opening) to let in the right amount of light to correctly expose the picture.

If the exposure isn't brief enough, the change in the subject's position while the lens is open will cause your subject to appear blurred.

How fast the shutter speed needs to be will depend on the velocity and direction of the motion you're trying to stop. The faster the motion, the faster the shutter speed needed to stop it. And it needs to be faster for subjects moving at right angles to your shooting position than it does for subjects moving towards or away from you. However, with subjects moving toward or away from you, it's more challenging to keep your subject sharply in focus. Some advanced cameras have intelligent auto-focus systems that track subject movement and adjust focus on the fly.

It might take nothing faster than 1/125th of a second to freeze baby as she totters toward you. But to stop a hurdler in mid-air flying past your camera position, you'll need 1/500th of a second or faster. If lighting conditions don't allow for a sufficiently fast shutter speed, try adjusting the camera's ISO setting, which controls the camera's sensitivity to light. Many cameras have this adjustment. A higher ISO setting will allow you to use a faster shutter speed, but will also

increase picture noise — a grainy effect that detracts from colour purity. But increased noise is a price worth paying if that's what it takes to capture the picture.

Plan the shot. Scout positions where you can catch anticipated action: a stock car passing, a scramble in front of the net, a slam dunk at the basketball game, the skater coming off a jump. Try for an uncluttered background.

And pre-focus. A digital camera can take close to a second to lock focus on a subject. When you pre-focus, you perform this step in advance, so that there's a much shorter lag between the time you press the shutter release and the time the picture is captured. If you don't pre-focus, your photo opportunity may have passed by the time the camera snaps the picture. To pre-focus, aim your camera at something the same distance away

as your subject will be. With most cameras, you press half-way down on the shutter release to activate auto-focus. Frame the picture while holding the button down and wait for the subject to enter the frame. Press down fully on the shutter release a split second before the magic moment.

The faster the shutter speed, the less light gets through to strike the camera's sensor. If lighting conditions are good (bright sunshine, for example) no problem. The camera will open the lens just wide enough to ensure proper exposure.

But lenses can only open so wide. In less than bright conditions, it may not be able to open wide enough. Using flash can help. You'll have to switch to some mode other than shutter priority, and select Auto or "fill" flash.

Even though the shutter speed for flash synchronization is typically only 1/60th, 1/100th or 1/125th (not very fast) the flash will illuminate the scene for much less time than that, so you'll still freeze the action.

With very fast motion, however, you may get dark ghosting, because available light will be sufficient to record changes in the subject's position.

Tip: You typically can't use multi-shot modes with flash. It takes too long for the flash to recover between shots.

The flash units built into digi-cams can generally illuminate subjects no more than 12 to 20 feet away (check your camera's technical specs). If you're 100 feet from the action or even 50, don't bother with flash. It won't help.

One solution is to buy a more powerful external flash that will extend your flash range, though never to 100 feet. Makers of some advanced digicams offer optional external flash units that attach to a hot shoe on top of the camera.

Motion-blur and action-tracking techniques were combined to produce this dramatic image of a racing car. The photographer used camera panning to follow the car and blur the background; but a slow shutter speed caused some blurring in the car, producing an exhilarating feeling of speed.

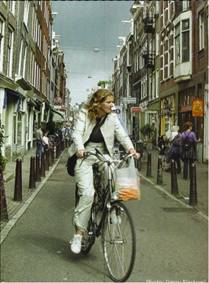

As this shot of a cyclist in Amsterdam illustrates, it's easier to freeze action when the subject in motion is moving towards you.

You may get better price-performance with a flash unit from a third-party supplier such as Sigma, Vivitar or Metz. But check carefully before buying to ensure full compatibility with your camera. Using an incompatible flash, particularly older models with high trigger voltages, can damage the sensitive electronics on digital cameras.

Many digicams won't accept an external flash directly. However, some third parties, such as Metz, make external flashes that are triggered by your camera's internal flash, so that you can shine more light on distant subjects.

Here's How to Create Motion Blur

Create a vivid impression of speed with judicious use of motion blur. It's an easy enough effect to create. Motion blur is what happens when you don't choose a shutter speed fast enough to freeze action.

Ideally, the main subject is slightly blurred but everything around it is sharply focused. A race car or bicycle speeding past your camera position will draw a comet tail of blurred streaks behind it.

It's no coincidence that image editing programs always provide a special effect filter to add motion blur to photos, because it's a cool effect. But it's better if you do it in the camera.

Again, you need to be able to control shutter speed. Choose a speed of 1/30th of a second or slower. Again, the right shutter speed will depend on the speed and direction of the movement.

Holding the camera steady in your hands at this speed is difficult, though sometimes you can manage it. I took the picture of the subway train entering a station in Montreal with a shutter speed of one second!

Steady the camera the best you can against your body (or brace it on an available flat surface), take a deep breath, wait for your body to stop twitching and then press gently on the shutter.

The alternative: use a tripod. I've taken to carrying a lightweight, compact tripod whenever I'm photographing. My Giottos RT-8000 ($50) weighs just 530g (18.5 oz.) and folds to 280mm (11 in.)

Tip: Jerking down on the shutter button, especially when using a lightweight tripod, can move the camera, blurring the whole picture. Make sure the tripod is firmly set, press gently, use a sturdier tripod or, best of a/I, use the remote shutter release if your camera came with one.

Here's How to Track Action

Tracking shots also create a vivid impression of speed and action. This time the main subject is in more or less sharp focus and the background appears blurred by motion. It's as if the viewer is moving with the subject.

Create this effect by tripping the shutter as you track or follow a moving subject in the camera's viewfinder.

Here's how. Set the camera to a slow shutter speed: 1/30th or even 1/15th of a second to ensure the background will be blurred. Figure out where to stand to best track the motion, and pre-focus as described above.

Use your digicam's optical viewfinder. You can't trust electronic viewfinders and LCDs to give you an accurate read on where a moving subject is in relation to the camera. Try for a dark, uncluttered background.

Tip: Plant your legs firmly in parallel to the path of the motion you're tracking and move only your upper body to keep the sub-

ject in the frame. Try not to jerk the shutter.

This is a skill. It will take practice. If you don't do it right, you'll get very blurred backgrounds and main subjects almost as blurred, clearly not what you want.

Here are two shortcut solutions.

If you have a sturdy tripod with a fluidly moving head, mount your camera on it and track using the tripod. It may feel awkward moving the tripod head, looking through the viewfinder and clicking the shutter all at the same time, but it can cure wobbly handheld tracking that blurs the main subject.

Another solution: if your camera allows slow shutter speeds when using flash, track the subject with the camera handheld, but use the

camera's slow or synch flash setting with a shutter speed of 1/8th to 1/15th of a second. The flash will freeze the moving subject, the long exposure will ensure a blurred background.

Slow flash is primarily intended to let you shoot at night and properly illuminate a foreground subject while making a long enough exposure to record highlights in the background.

Typically, the flash fires when the lens is first opened and then the lens stays open to record the background. But some cameras let you choose an alternate mode in which the flash fires just before the lens closes. That's the one you want.

With the more typical slow flash mode, if you don't track at exactly the right speed, you'll get a streaky, ghost image of the moving subject ahead of its trajectory. Using the second slow flash mode will move that comet tail behind the subject where it logically belongs.

In the low light of a Montreal subway station, a shutter speed of one second created motion blur in the onrushing train. (above)

A bicycle speeding past the camera in Vienna becomes a bright blur against the sharply etched background. (left)

Challenges

Mastering these techniques will not, unfortunately, ensure pro-quality action shots in all the situations you might like. Getting dose enough for good pictures at hockey arenas, football fields and ball diamonds often requires a long lens or difficult-to-secure vantage points.

Trying to shoot hockey action, even minor-league hockey action, can be particularly frustrating. In city arenas in our area, the ice surface is sealed behind high glass. You can shoot through it, but the glass is smudged with puck rubber and scratched, and you can't use flash effectively because some of the light will bounce back off the glass.

Your best option is to get permission to set up at a bench or in the time-keeper's box, though both positions are too far from the nets (where the most exciting action happens) if you don't have a powerful telephoto lens.

One solution? Don't aspire to be a pro sports photographer. Look for action on the street: skate boarders, bicyclists, pick-up basketball games, T-ball at the local park. Or look for ways to dramatize action in every-day life. You can even create neat effects shooting people walking or sparrows fluttering around a bird feeder. <•

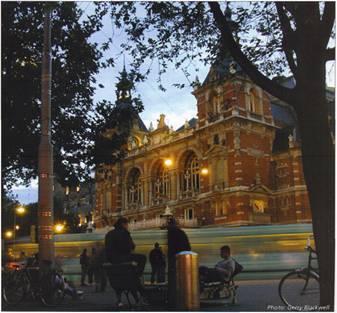

A passing Amsterdam streetcar becomes a green blur in this picture taken with a shutter speed of two seconds, with the camera braced on a cafe table.

Back to Menu