Guide to candid and city photography

Friends and family frequently look at photos I've taken, often the ones I'm proudest of, and say disappointedly, "Who is it?" or "Do I know them?" or "Where is that!" The pictures are usually candid and street-level shots I've taken in public places. It's the kind of photography I most enjoy doing, but it's not what people expect or want from snapshots.

I don't mean "candid" as in Candid Camera: lurking in a hiding place, hoping to catch people making fools of themselves. I simply mean unposed and natural. It's true a little subterfuge sometimes helps to distract subjects from the presence of the camera so they

will be natural, but a photographer can hide in plain sight too, something we'll talk about later.

It doesn't have to be strangers in public places either. To me, unposed and natural are the characteristics of all good photographs - even portraits. Candid is what photography does best. You grab a fleeting moment in time - a real moment, not a staged moment -and fix it forever.

Some of the most iconic photographs ever made are icons because they appear to be so spontaneous and real; though sadly, some may be staged. Think of Alfred Eisenstaedt's famous black-and-white photo of the American sailor in Times Square bending a girl backward with a

kiss to celebrate victory in World War II. Or Ruth Orkin's American Girl in Italy, with an anxious, waifish young woman walking alone down a street lined with leering men.

For the real thing, seek out the work of the great French photographers Henri Cartier-Bresson, Andre Kertesz and Jacques-Henri Lartigue, the Americans Harry Callaghan and Roy DeCarava, and the Hungarian-born war photographer Robert Capa, to name just a few (see "Studying the Masters").

Another closely-related genre of photography I enjoy is street scenes and images that record the ambience of a place. It could be any place, by the way, even your own neighbourhood. Check out some of the same masters to see how it's done when it's done and add to that list artists like Frederick Henry Evans and ec Steichen.

You don't have to be a master to take pleasing candid shots and interesting street scenes. Nor do you need special equipment. And you don't have to go to exotic locales either. You just need a good eye and the patience to watch and wait for the right moment.

Stealth Shooting

If you're using a digital earner taking candids especially may little easier. Digital cameras are typically smaller than traditional 5mm SLR cameras, so less obtrusive.

using a camera with

a swiveling viewfinder, the photographer was able to take a

picture of a bored Costa Rican boy without him being aware he

was being photographed.

using a camera with

a swiveling viewfinder, the photographer was able to take a

picture of a bored Costa Rican boy without him being aware he

was being photographed.

And if your digicam features a Iting LCD viewfinder, as many do, means you can hold the camera )w to your body where it's less oticeable. It's tough to go unno-ced with a behemoth of an SLR rowing out of your face.

Another nice thing about digi-ams for candid shooting: you can jrn off the electronic sound ffects and shoot silently. Clicking ie shutter on an SLR creates a ter-ble clatter of mirrors folding up iside the camera body to clear a iath for light. You might get one hot off unnoticed in quiet sur-aundings, but rarely a second. Vith digicams and, to a lesser xtent, rangefinder film cameras, ou can be very sotto voce.

I confess to being a shy photog-apher most of the time. I'm sure ithers are too. I miss many shots d love to get for fear of offending ieople who might notice me tak-iq their picture. I imagine them wunding across the space letween us, grabbing my camera md smashing it to the ground, or ihysically attacking me. Or just peaking sharply to me. (I'm a vimp, I know.)

If you feel the same way, take leartfrom what braver photogra-ihers say, and what limited experi-'nce has taught me: very often trangers not only don't mind you aking their picture, they actually 'njoy it. Of course, you don't want trangers clowning for your cam-fa any more than you want your riends and family doing it. Then it's not candid photography any-nore.

Under the law in Canada and in many other jurisdictions, people in public places are considered to have no reasonable expectation of privacy, so cannot claim you are invading their privacy if you take a picture. That said, it's always a good idea (and just good manners) to be sensitive to how people feel about being photographed, especially if you're in a foreign country, or any milieu where you're a stranger.

Some people genuinely don't want to be photographed. Some may scowl when they see your camera and keep scowling, but do or say nothing. Others will surprise you by changing from scowling to smiling the minute the camera points at them. And then there are the psychopaths of my imagination.

One way to beat the shy factor, of course, is to use a long telepho-to lens. Some digital cameras come with 10x or even 12x optical zoom lenses that let you capture images from a very safe distance. I always think that's a bit of a cheat, though, a bit Candid Camera-ish, unless it's really the only way to get close enough to your subject.

Telephoto lenses are also generally slower than shorter focal lengths (i.e. the lens doesn't open as wide), so they require slower shutter speeds. This means if you're shooting handheld, you need stronger light to do it effectively. The blurring effects of hand shake, always a risk when shooting at shutter speeds of 1/60th of a second or less, are exaggerated when using a telephoto lens. It's also harder to hold a camera steady when it's overbalanced by a long lens.

Bottom line: you may need to use a tripod, which even at a distance can make you a little conspicuous.

A stairwell between photographer and these two women at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art made it easier to take this picture, even though the older woman appeared less than pleased.

Creating Distance

Sometimes, if you're lucky, even when the distance as the crow flies between you and your subject is short enough to get a good shot without a long lens, circumstances put you at enough of a remove that you can feel comfortable pointing the camera. Take a look at the picture of the two raven-haired women leaning on a half wall at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

I felt bold enough to take this picture, even though the older woman was looking right at me and appeared less than pleased, because there was a stairwell and atrium between us. I could be long-gone before they ever got to where I was standing.

Windows are also good barriers, although managing reflections can be tricky. I was lucky in that respect with the picture I took of a Chinese cook through a plate glass window at a Manhattan eatery. The reflections worked well. I could have made a better picture, though, if I'd had the nerve to wait for him to look up and see me.

If you're the shy type, you may also find, as I do, that it's easier shooting in busy urban settings where there's lots going on, especially in tourist places where people with cameras are a common sight. Nobody pays attention to you because there's so much else going on; or if they do notice, you're nothing out of the ordinary.

Consider the picture I took of a gypsy jazz band playing on the street in a small tourist town in the south of France. I had no compunction about getting fairly close and taking the shot, partly because I knew the musicians would be unlikely to object and partly because their attention, and the audience's too, was on the music. One of the band members did look right at me as I clicked the shutter, which was exactly what the picture needed.

There are lots of situations, though, where you don't have the luxury of a tacitly willing subject and lots of distractions to make you invisible. One dodge I've tried a few times is to find a pretext for taking a picture of one thing while actually taking a candid shot of something or somebody else that just happens to be included in the frame.

It usually takes a wide-angle lens or a zoom lens with a moderate wide-angle setting to do this. Digital cameras with swiveling or flip-out LCD viewfinders can also be useful. Some allow you to have the camera pointed one way while you appear to be looking another, even though you're actually looking in the viewfinder. With luck, your subjects won't even know they're being photographed.

The shot of three riders on a Manhattan bus is an example. The one in the middle is my daughter. I had been talking to her a few moments before; and as far as the other two women knew, I was taking a picture of her. It was them I wanted, of course. I think the one on the left knew what was going on. She has a kind of "who're-you-trying-to-kid" expression.

Windows are good

barriers for candid photography, although managing reflections can be tricky.

In this picture of a Chinese cook at a Manhattan eatery, the reflections create

a context for the photo.

Windows are good

barriers for candid photography, although managing reflections can be tricky.

In this picture of a Chinese cook at a Manhattan eatery, the reflections create

a context for the photo.

The Perfect Moment

Sometimes you do have to fake out your subject. Once in Costa Rica, in an almost empty restaurant, I spied the young son of a kitchen worker, looking lonely and

bored on his Christmas holidays. He was watching cartoons on a TV high up on the wall while his mama worked. The little guy noticed us too and seemed a bit leery of my digital camera. How to take him unawares?

I set the camera, a Nikon Coolpix model with a nifty swiveling lens assembly, on our table at arm's length, as if I wasn't using it just then. But I pointed the lens at the boy and from where I was sitting, I could see him in the LCD viewfinder. Eventually he turned towards us as the cartoon ended and I got a shot off. It took about 15 minutes. The result is no prize-winner, though it does tell a story. I call it "That's All Folks." The point is that half the fun of candid photography sometimes is the process, the hunt for an original image.

I believe the best candid shots are the result of patiently waiting for something to happen and capturing it, at close range, at the exact moment it does. To do this well, you need to learn techniques for hiding in plain sight. One is to just hang around taking innocuous pictures until people get used to your presence. Sometimes you can become almost invisible.

You need to prepare your camera too. If you know the direction in which you'll be shooting and the prevailing lighting conditions, you can set the aperture and shutter speed ahead of time. And even pre-focus if you know approximately where your subject will be when whatever is going to happen happens. Then you can shoot without hesitation when the moment arrives.

Harry Callaghan took a famous series of candid shots of people on e street in Chicago in the 1950s by setting up his camera, pre-focusing, holding the camera at a fixed height and then firing, with-jt even composing, as he saw a likely subject approach the point here he knew they would be in s frame. The published results are surprisingly powerful: informal, ten very close-up, portraits of people caught unaware, vulnerable. Candid shots don't have to be character studies. Sometimes you in make interesting pictures with just somebody's back in them - or blur. Or nobody at all. Take a look at the picture of the main staircase at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The completely anonymous and slightly burry figure striding out of the frame at the left makes an interest-g counterpoint to the huge Roy Leichtenstein pop-art painting hanging on the wall - of people climbing the same staircase.

This picture of the main staircase at New York's Museum of Modern Art, the blurry figure makes an interesting counterpoint to the painting on the wall - of people climbing the same staircase.

As noted at the outset, candid isn’t just for anonymous subjects. Even when you're shooting a portrait, catching your subject in an unguarded moment usually produces better, more telling results than when the subject self-consciously engages the camera. Some portrait photographers use little ruses like telling the subjects to relax for a moment while they adjust the camera. Then they take the picture when the subject least expects it.

The figure in the middle of this shot is the photographer's daughter. As far as the other two women knew, the photographer was taking a picture of her. But the one on the left has a kind of "who're-you-trying-to-kid?" expression.

Street Life

Some of the same principles apply when shooting streetscapes and architecture. If you want to capture street scenes in which people are going about their business unselfconsciously, you'll need to blend in. And when people (and vehicles) are in motion, you have to wait for the precise moment when all the moving objects in the scene are in the exactly right position for a good and telling composition.

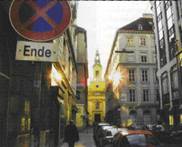

Again, you're looking for that frozen-in-time effect. Take a look

at the shot of the bicyclist coming out of a pedestrian street in downtown

Vienna, Austria. Blending in was no problem here (this is a tourist city), so I

had plenty of time to compose. Composition

is another key to good street and architectural photography. How

successful was I here?

Again, you're looking for that frozen-in-time effect. Take a look

at the shot of the bicyclist coming out of a pedestrian street in downtown

Vienna, Austria. Blending in was no problem here (this is a tourist city), so I

had plenty of time to compose. Composition

is another key to good street and architectural photography. How

successful was I here?

I like the way the picture freezes the cyclist and the separate groups of tourists in the background: it almost looks like a movie set just after the director has shouted, "Action!" But is the bicycle in the best position for an optimal composition? Closer to the camera would have been better, and I don't like the way it overlaps and obscures the female cyclist behind: it weakens the focus on the main figure.

Also, street scenes often include sky. In this shot, because I wasn't using a polarizing filter and probably didn't choose the optimal exposure settings, the foreground, mid-ground and background objects are all reasonably well lit and exposed, but the sky is overexposed and has become a white triangle with no detail. It's distracting because the eye tends to shoot up it and out of the image.

The same problem mars another scene from Vienna. In this one, I used an easy trick of composition, worth remembering. Shoot straight down a narrow street to an object of interest somewhere along its length: it could be a person walking or, as in this case, a notable building. The clear lines of perspective draw the eye to the yellow church. The starbust reflections of the late afternoon sun off buildings along the street add to the composition. But again, the eye tends to shoot out of the top of the frame because of the blank sky.

Solutions: use a polarizing filter, which reduces the glare that is partly responsible for the effect in these images, and/or slightly under-expose everything else so the sky is closer to being correctly exposed and therefore retains more detail and colour. If you're using a tripod, there is a trick you can try that requires some post-processing. Shoot two pictures from the same set-up: one with the area below the horizon properly exposed, one with the sky correctly exposed. Then in Photoshop Elements or some other photo-editing program, selectively merge the two shots to combine

the correctly exposed elements from each in the final image.

Cityscapes

The clear lines of perspective in this shot,

taken on a narrc street in Vienna, draw the eye to the yellow

church.

The clear lines of perspective in this shot,

taken on a narrc street in Vienna, draw the eye to the yellow

church.

When shooting in big cities, I'm often attracted by the juxtaposition between old and new architecture, and also by the effects of mirrored modern facades, though both have become photographic clichés.

Sometimes you can combine the two to create interesting abstract images. In yet another shot from Vienna, I caught a wavy reflection of a cathedral spire in the curved glass facade of a nearby building.

Whole books have been written about architectural and cityscape photography, but here are a couple of very general tips. Try to shoot in late afternoon or early morning light; both make buildings in particular, but really any subject, look more attractive. Use a tripod whenever possible. Usually you want lots of sharp detail throughout the image when shooting buildings and streetscapes; and that means using the smallest aperture (biggest f number, e.g. f/11) to get maximum depth-of-focus.

The wavy reflection of a cathedral spire in the curved glass facade of a nearby building provides an interesting juxtaposition of old and new.

Except in the brightest light, if you stop the lens all the way down (choose the smallest aperture), you'll be stuck with a shutter speed so slow it will be difficult or impossible to shoot handheld without blurring the image. And as noted, you generally get more attractive results shooting in weaker late or early light.

Another reason to use a tripod: to capture motion effects in low light. Frame a picture that includes buildings and other static objects but also includes people or vehicles passing. Expose for the static objects, using a deliberately very slow shutter speed (a second or less) and you'll capture lots of detail in the buildings but also get interesting effects created by vehicle tail lights or ghost-like mobile pedestrians.

Composition, as noted, is key. Keep compositions as simple as possible. That's not always possible in a busy urban setting, but you want a strong central focus: central as in most important, not necessarily in the centre of the frame. Though it's often difficult, try to avoid cutting off interesting objects or buildings at the edges of the frame; it tends to distract the viewer's focus on the main subject.

The best building pictures often show close-up details of a structure - the gargoyle on a medieval church or the fancy lintel over a street door, for example. Also try experimenting with abstract shots using a telephoto lens or zoom setting that compresses perspective so that objects in the scene appear to be closer together than they are. But be sure to also shoot more conventional "establishing" shots from a greater distance or with a wider-angle setting to show the whole scene.

As usual, we've only scratched the surface of what it's possible to say about the subject. And also as usual, the very best advice is to get out and shoot. Don't wait for your next trip. Go out and shoot your own city and its people. And don't be shy. •

Back to Menu